est Read online

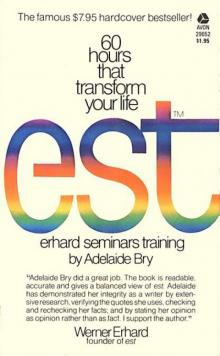

Get it: est WORKS! That's the news that est graduates all over America are eagerly telling their friends, families, co-workers, and just about anybody else who'll listen. Thousands have taken the est training so far -- including such celebrities as John Denver. Valerie Harper, Cloris Leachman, Joanne Woodward, Yoko Ono, and Jerry Rubin -- with Incredible results. ______________________________________________________ In this remarkable book -- the first full-scale, totally honest look at the est phenomenon -- you'll read per- sonal statements from est graduates who reveal inti- mately what the training h.as meant for them -- how dissatisfaction has become satisfaction, how rela- tionships have improved dramatically, how physical problems (from overweight to insomnia to allergies) have been transformed into vibrant health -- all this with no effort at all, in just two 30-hour weekends. est: 60 Hours That Transform Your Life gives you a wealth of facts and vital perspectives on the most powerful new growth experience In America -- important reading forest graduates and non-graduates alike, and must reading for anyone who wants to get real and continually expanding satisfaction out of life! 60 hours that transform your life est erhard seminar training by Adelaide Bry AVON PUBLISHERS OF BARD, CAMELOT, DISCUS, EQUINOX AND FLARE BOOKS. Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following: Excerpts from East West Journal interview with Werner Erhard reprinted by permission of East West Journal. Lyrics from "Looking for Space" by John Denver reprinted by permission of Cherry Lane Music Co. Copyright 1975 Cherry Lane Music Co. (ASCAP). All rights reserved. AVON BOOKS A division of The Hearst Corporation 959 Eighth Avenue New York, New York 10019 Copyright © 1976 by Adelaide Bry Published by arrangement with Harper & Row. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 75-30329 ISBN: 0-380-00697-9 All rights reserved, which includes the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Harper & Row, 10 East 53 St., New York, N.Y. 10022 First Avon Printing, August, 1976 AVON TRADEMARK REG. U.S. PAT. OFF. AND FOREIGN COUNTRIES, REGISTERED TRADEMARK -- MARCA REGISTRADA, HECHO EN CHICAGO, U.S.A. Printed in the U.S.A. To my parents and their parents who were still concerned with most of the three feet, and to my children, Barbara and Douglas, and to their children, who will be able to experience that last quarter inch "Adelaide Bry did a great Job. The book is readable, accurate and gives a bal- anced view of est. Adelaide has demon- strated her integrity as a writer by extensive research, verifying the quotes she uses, checking and rechecking her facts, and by stating her opinion as opinion rather than as fact. I support the author." -- Werner Erhard Acknowledgments Marjorie Bair and Herb Hamsher, you are both fabulous. Your assistance with this book was beautiful. Thank you. I love you. In New York and California and points in between, I send my love to all the est graduates who shared their experi- ence of est with me; and especially to Lea, Christian, Rick, Cathy, Morgan, Fred, Lee, Nessa, Bill, Ted, John, Jim, Bob, Alfred, Brad, Phyllis, Stephen, Judy, Carol, Michael, and Brunhilde. Thank you. Thanks to Dr. Edward Blair Guy for my official introduc- tion to the Federal Correctional Institution at Lompoc. Thank you, Werner, for creating est, and thank you, est and Morty Lefkoe, for assisting me in getting the facts. To Alice Kenner and Nancy Cone, of Harper & Row, thanks for editorial excellence and grace under pressure. Contents Cheese 1. How's Your Life? Gerry and Marcia 2. In the Beginning Father Joseph Brendler 3. Beliefs Jim 4. The Training Margot 5. Volunteering and Vomit Bags Richard M. Dawes, M.D. 6. est Goes to Prison Jason 7. Tots, Teens, Grads, and Others Janet 8. Werner and His Business Aunt Anna and Uncle Harry 9. Something About Nothing Bailey 10. Where Werner Comes From: Grist for the Mill Felice 11. The Future Dennis Shorthand: A Glossary "Looking for Space" est ™

Cheese "Obviously the truth is what's so. Not so obvious, It's also so what." -- Werner Erhard

If you put a rat in front of a bunch of tunnels and put cheese in one of them, the rat will go up and down the tunnels looking for the cheese. If every time you do the experiment you put the cheese down the fourth tunnel, eventually you'll get a successful rat. This rat knows the right tunnel and goes directly to it every time.

If you now move the cheese out of the fourth tunnel and put it at the end of another tunnel, the rat still goes down the fourth tunnel. And, of course, gets no cheese. He then comes out of the tunnel, looks the tunnels over, and goes right back down the cheeseless fourth tunnel. Unrewarded, he comes out of the tunnel, looks the tunnels over again, goes back down the fourth tunnel again, and again finds no cheese.

Now the difference between a rat and a human being is that eventually the rat will stop going down the fourth tunnel and will look down the other tunnels, and a human being will go down the tunnel with no cheese forever. Rats, you see, are only interested in cheese. But human beings care more about going down the right tunnel.

It is belief which allows human beings to go down the fourth tunnel ad nauseam. They go on doing what they do without any real satisfaction, without any nurturing, because they come to believe that what they are doing is right. And they will do this forever, even if there is no cheese in the tunnel, as long as they believe in it and can prove that they are in the right tunnel.

People who are getting satisfaction out of life don't have to prove they are in the right tunnel. Therefore they don't need beliefs.

Belief is all you have when you're not getting satisfaction in your life.

This Werner Erhard story, familiar to most est graduates, is an introduction to a simple but basic notion -- that one's beliefs about reality may have no relationship to what is really happening.

Get it?

1

How's Your Life?

"Man keeps looking for a truth that fits his reality. Given our reality, the truth doesn't fit." -- Werner Erhard

How is your life working right this minute? Do you believe that it would be better if you had more money? A different spouse or lover? Bigger and better orgasms? More respect, or responsibility, or income? Would it be better if you had better looks, brains, figure? If you were better liked? Or if, as a child, you had received more love, kindness, education, or opportunity?

Undoubtedly you can answer "yes" to at least one of the above. How nice, then, to know Werner Erhard has said, "I happen to think that you are perfect exactly the way you are." He goes on to say, "The problem is that people get stuck acting the way they were, instead of being the way they are." So if it's "getting better" that you're after, you're stuck in a belief about "getting better." Getting better, however, is not what est is about.

If est isn't interested in changing people, what does it do? What is this process that has so far trained 75,000 men, women and children and whose founder and leader has stated that he intends to train forty million?

From one point of view, est can be seen as beginning where everything else leaves off.

Starting with Freud, and followed in short order by other systems that were variations on Freudian themes, contemporary Americans have become accustomed to the notion that they can talk, reason, or scream their way out of problems or neuroses and into sanity, or wholeness.

After World War II, psychoanalysis became the change agent for those who could afford it. But that method of getting in touch with childhood experiences and of eradicating or accepting whatever mother, father, and environment had "done to" us is extremely costly and often doesn't work. Understanding one's past doesn't necessarily lead to change. And often, screaming doesn't either.

est clearly states in its general information brochure that "it is not like group therapy, sensitivity training, encounter groups, positive thinking, meditation, hypnosis, mind control, behavior modification, or psychology. "In fact," the statement concludes, "est is not therapy and is not psychology."

Implicit in those words is the premise that what they're offering is something quite different. It

was a search for something I was not yet able to define -- something beyond the psychologies, something "quite different" -- that led me to est.

I first learned of est through a young friend who called excitedly from California to tell me about it. She was certain that I'd be interested in what she described as "this latest head/body trip" because of what she knew about my other involvements.

In addition to being a practicing psychotherapist and a writer, I am a seeker of truth, self-realization, and spiritual and physical highs. You name it -- in terms of self-improvement discipline, and chances are I've done it. I've studied yoga and transcendental meditation. I've been Rolfed and psychoanalyzed. I've "done" nude marathons, encounter groups, transactional analysis, Gestalt, guided LSD trips, and Silva Mind Control. Most recently, prior to est training, I went through the heady forty-day Arica training.

I had experienced much of the growth (sometimes called "grope") movement of the sixties, had undergone some important changes, but was still hungry for more.

In my quest for growth, for meaning, for inner change, I was but one of many searching for surcease from the malaise that increasingly has marked middle-class America since World War II. I, like many others, was searching for satisfaction.

The affluence that had been so ambitiously pursued through the sixties in this country, and to a great extent attained, clearly wasn't living up to its promise: happiness ever after. As more and more of us bought ourselves swimming pools, foreign vacations, and early retirements, both the divorce rate and the crime rate soared.

Two cars in a suburban garage didn't seem to change our feelings of loneliness, alienation, disappointment, or despair. Nor did the divorce or affair that often followed, because they were responses to symptoms rather than to causes.

Another sacred cow, education -- and especially college education -- also turned out to promise more than it delivered. The expectation was that the young, their heads crammed with information, would emerge from school equipped to create better or happier lives than their parents had. The fact was that a lot of theso youngsters rejected their parents' work and moral ethics, creating still further alienation.

Along with money, education, and status, the sacrosanctity of the family also began to be questioned. As the extended family became a thing of the past, and nuclear families experienced increasing isolation in their suburban homes and urban apartments, the task of rearing the children fell almost completely to the woman parent. This proved an incredibly heavy burden for both mother and children, and they suffered and suffocated in it, while fathers grew more remote.

Cornell University social psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner noted in a Newsweek cover story on the contemporary family that the incidence of family pathology is spreading swiftly among all sectors of U.S. society. "The middle-class family," he said, ". . . is approaching the level of social disorganization that characterized the low income family of the early 1960's." *

* September 22, 1975.

According to the same article, teen-age drug abuse and alcoholism are also on the rise. Suicide has become the second leading cause of death among young Americans between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four, and the rate of juvenile delinquency is increasing at such a pace that today one child in nine can be expected to appear in juvenile court before the age of eighteen.

To chronicle the ills of the past couple of decades, by way of understanding how we got to est is not my purpose here. Suffice it to note, at the risk of sounding simplistic, that our values are breaking down in all areas -- relationships, education, economics, politics, etc. -- and that out of this crisis new alternatives are being sought.

Many of us have become, like myself, seekers of a better way -- a way out of the confusion, the complexities, the uncertainties that seem greater now than ever before.

This search is reflected in such items as the fact that every suburban community has its yoga class; in the incredible sales figures of books on mediums (Edgar Cayce), magicians (Don Juan), and mystics (Sri Aurobindo, Chogyam Trumpa Rinpoche); in the fact that whole families take the phone off the hook before dinner for twenty minutes of transcendental meditation (at last count more that 450,000 people have studied TM); and in the consciousness expansion still sought through such hallucinogenic drugs as LSD and mescaline.

A friend of mine, married to a longshoreman, is studying Tai Chi and is heavily into its philosophy. A businessman I know is using biofeedback to reduce his blood pressure. And a woman with whom I once pushed baby carriages leaves a luncheon early to meet with her Zen master. It's no longer unusual to encounter people who have left careers they sweated for, because the work or the goals were no longer "meaningful." I did it -- as have a-half a dozen friends in their middle years.

These reports of individual experiences are not isolated ones. They have become part of a spontaneous movement called the "consciousness revolution." The movement is taking many forms, going in many directions, and has many spokesmen. Many see it as the beginning of the New Age, a time in mankind's evolution which has been prophesied for centuries and which is both an end and a beginning; a critical point in history in which man and his planet are undergoing vast transformation.

This new consciousness, essentially an experience of self, ranges from a new experience of one's body to a new experience of God -- which is not, as it may appear, contradictory. When Time magazine in a 1969 cover story proclaimed that God was dead, it was talking about the all-powerful Judeo-Christian God, who might zap us (that is, send us to hell) if we didn't behave ourselves. It was a God beyond us, a Father whose love was conditional.

The God of the seventies is out of the Eastern tradition. It is God within, and thus God and the self are inseparable. One can experience God directly, and thousands are doing just that daily through such consciousness-altering techniques as meditation and chanting.

William Irwin Thompson, in his brilliant exploration of the new planetary culture, Passages About Earth, writes, "A new ideology is being created . . . Perhaps it will take no institutional form at all, for it now seems that social institutions are no longer adequate vehicles of cultural evolution. We cannot go to church to find radiant Godhead, to the army to find glory in war, or to the universities to find aesthetic transfiguration or wisdom. Now only mysticism seems well suited to the postinstitutional anarchism of technetronic culture, on the one hand, and the infinite posthuman universe on the other." *

* New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

And Marshall McLuhan, in a Playboy interview (March, 1969), speaks of the imminence of "the universality of consciousness foreseen by Dante when he predicted that men would continue as no more than broken fragments until they were unified into an inclusive consciousness." This new conscidusness, he says, is now possible with the development of the electronic media.

If cosmic consciousness is the goal, then inner experience is the means. Futurists such as Thompson and McLuhan are talking about the mystic intuitive experience. Others are focusing on the feeling experience. (Note that no one is talking about the intellectual experience, which is becoming as passé as psychoanalysis.)

Part of how you feel is how your body feels, which of course is directly related to how your feelings feel. Wilhelm Reich's theories of character armor (body defense against feelings) and the flow of energy within the body foreshadowed the current Western interest in such systems as bioenergetics, the Alexander technique, Rolfing, Hatha Yoga, and Shiatsu. All these techniques seek to liberate the body and focus on inner well-being as opposed to outer success.

Esalen, the number one growth center of the sixties, is now concentrating on increasing body energy toward flowing with the universe. Among their "new" techniques: tennis and golf!

Those deeply into body techniques claim that the story of our lives is stored in aching muscles, low back pains, headaches, and all the other aches we try to eliminate with tranquilizers, sedatives, and painkillers, drowning our feelings in order to "feel better."

In ac

cepting the fact that body feelings are inseparable from emotional feelings, the question "How do you feel?" becomes more relevant today than ever.

When I was a child, I wouldn't dream of telling people what I felt unless it was an "up" feeling, nor would I divulge my feelings about another person unless they were positive. But it was O.K. to describe the bellyaches and headaches that resulted from the fear or anger or other taboo emotions I couldn't talk about.

Nowadays people express their feelings about rage, sex, sorrow -- you name it -- with the ease that their parents once talked about the weather. Which may be one of the factors that led Jean-Paul Sartre, in a recent interview, to predict a future "transparent man" in whom a thought would be immediately visible, eliminating the need or desire to hide it or pretend another.

The keynote of the present is in the words "unity" and "integration." Thus, the new disciplines seek to integrate mind, body, and soul -- how we sit, the way we breathe, what we eat, what our inner voices tell us, how our gut reacts, who we really are -- so that we can experience our totality, our wholeness, our oneness with the universe.

A lot of this may not sound especially new and, in fact, a lot of it isn't. What is new is the way it is becoming known. In Arica,* I went through meditations and special exercises to experience my oneness with all living things and my harmony with the vast universe. In the past, the closest I might have come to this understanding was by listening to someone pontificate from a pulpit or lectern on the ways of God.

est

est